Collecting cards and sports memorabilia isn’t a new hobby. Baseball cards first appeared in the late 1800s. However it would be almost another 100 years before people started buying cards for the sole purpose of collecting them. Collecting reached a fever pitch by the early ’80s and it seemed the card companies couldn’t print enough to keep up with demand. So they came up with a simple solution: just print more; increase production and output to meet demand. But there’s a reason most governments do not increase the production or printing of national currency to settle debt: it devalues it.

The card companies at the time, Topps, Donruss, Fleer and, eventually, newcomer Upper Deck must have all been sick on the day their economics teacher explained why you can’t print more of something and expect it to keep its value. And so the most infamous era in collecting was born, The Junk Wax Era. The card companies came close to bankruptcy and nearly ruined a beloved hobby for so many. But how did we get here and what did the hobby learn from it?

The Junk Wax Era: 7 Years of Collecting That Almost Collapsed the Hobby

Generally considered to have lasted from 1987-1994, during the Junk Wax Era card companies were printing 3x as many cards as before. First, Barry Larkin, Mike Greenwell, Greg Maddux, Barry Bonds, Ruben Sierra, Rafael Palmeiro, Matt Williams, and Bo Jackson all had rookie cards in 1987. Other notable players whose rookie cards would appear in this era would include: Tom Glavine, Ken Griffey Jr., Alex Rodriguez, Derek Jeter, Omar Vazquel, Jim Abbott, Chipper Jones, Mariano Rivera, Frank Thomas, Jim Thome, Mark McGwire and more. Keep in mind that these are only the baseball players. Think of all the hockey, football, and basketball greats from this era too whose rookie cards came out during this time: Michael Jordan, Shaquille “Shaq” O’Neal, Jaromir Jagr, Barry Sanders, Troy Aikman.

Second, people started rushing out to buy complete sets and cases of these cards just to hoard them, hoping to one day to sell them off to pay for their kid’s college education or their own retirement. Much like holding onto a U.S. $2 bill, people were convinced these cards were rare and would increase in value over time. Most $2 bills are only worth $2 and are not rare. Most of the cards created during this period were so abundant thanks to the increased production and people who hoarded them, everyone had them. In fact, The New York Times even deemed baseball cards to be a wise part of a diversified investment portfolio in 1988. Respected and trusted publications like Beckett Magazine were valuing individual cards at 10x the cost of a pack and some investment firms were telling the public that sports cards are a smart investment that could pay more than bonds.

Further complicating things is that Beckett (and their competitors) may have intentionally been overvaluing cards and misleading readers. With no internet available, Beckett Magazine was the only way to check the value of cards. Naturally, if Beckett kept hyping up the value of the cards and the market for cards, this would lead to an increase in Beckett Magazine sales as eager investors needed to know how much cards were worth, what they should buy next, and when they should sell. Beckett listed most of these rookie cards as being worth $4-$8 a piece from the late ’80s to early ’90s. For a pack that only cost 50 cents or so at the time, this was a great return on investment (plus the piece of bubble gum!). To the best of my knowledge, Beckett has never admitted to any intentional wrongdoing or overvaluation during this time, but it is worth noting that monthly subscriptions to Beckett Magazine grew to over 1 million during these years, the highest the magazine has ever had.

Third, card collections were seen as a status symbol among young boys growing up. You wanted to be the coolest kid on the block? You had to have the biggest and baddest three-ring binder of nine-count plastic sleeves filled with only the best rookie and all-star cards and, if your allowance was $1 a week at 10 years old, packs of cards would have seemed like a solid purchase. Video games had just come into style, but $1 a week was not enough to buy a new one, and Pogs and Beanie Babies hadn’t caught on yet.

As for adults, they were hearing a lot of price tags and numbers. That same article above from the New York Times estimated cards had increased in value by 32% a year every year since 1978. A seller with what he claimed was a one-of-a-kind card was seeking $1 million for his 1932 Frank Lindstrom card. It was believed the set it came from only had 31 cards, however this Lindstrom was the 32nd card in the set, which the manufacturer had mistakenly labeled as canceled. One of the Holy Grails of cards, the 1909 T206 Honus Wagner, had sold for over $100,000 at auction. Now imagine how much collectors thought cards from the ’80s would be worth in 20, 30, 50, 75 years if the 32 Lindstrom and T206 were fetching such hefty prices!

What Did We Learn

The Junk Wax Era was mercifully ended by the baseball player’s strike of 1994. No players meant no cards. Collectors stopped buying cards because they had them all already and there was no motivation to buy duplicates. But because the companies were overproducing their production costs had gone up, including printing, shipping, and marketing. They were losing money, and a lot of it.

Economics 101 is when supply goes up demand goes down. That’s exactly what was happening with the cards. There were no autographed or jersey relic cards inside these cards; no inserts or refractors; no incentives. There was nothing to chase but a pipe dream that one day you could retire off these cards by reselling them. Card companies lowered production to normal levels. Although none of the major card companies released official numbers of how much they printed, it is estimated that between tens to hundreds of billions of cards were printed and distributed over roughly 7 years.

Today, you can probably buy these by the pound and every once in awhile you might find some sealed packs from this era for sale in Wal-Mart or a gas station (if you want about 3000, contact me, because I’ll be glad to send you mine as long as you pay for shipping). Of course there are some cards from this era that will cost you significant money, but for the most part these cards are not worth the paper they are printed on. I do not buy cards from the Junk Wax Era, personally. There’s no fun in it for me. They are before my time and 99% are worthless.

My advice to anyone who still has these cards is to cut your losses; burn them, give them out for Halloween, donate them to a children’s hospital, put them in your kid’s bike spokes. If anyone offers you money for your collection, take it and run. Don’t even barter or counteroffer. Just do whatever it takes to get them out of your house.

The Junk Was Era happened because of a perfect storm of breakout players and card-collecting fever. As Hall of Fame players started to breakout as rookies and make names for themselves, many experts were pushing cards as solid, valuable investments, and overproduction made the cards incredibly easy to find. The Junk Wax Era is arguably the greatest bubble to burst that economics has forgotten about. But at least the cards take up less room than Beanie Babies.

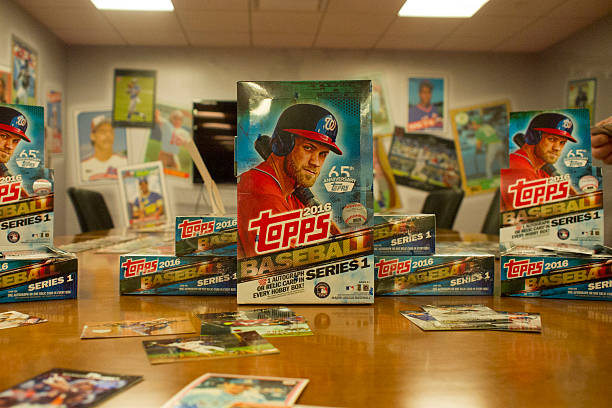

Main image credit:

I have to tell you this but it’s a common mistake made in most articles about this card era. 1987-1994 is 8 years, not 7. Count it out on your fingers if you don’t believe me. Just a pet peeve of mine. Sorry.

Hi Gabe, do you still have the 3000 packs you mentioned in the article? I’m looking to expand my collection. Thanks!