Lawrence Weschler was fresh off from California, starting a job with The New Yorker in the early 1980s. He had impressed the editors at the magazine with a profile on the contemporary artist, Robert Irwin. He moved to New York and quickly told the editors about his next profile. It wasn’t going to be a famous painter or artist in general, but medicine’s poet laureate.

The Early Days of Oliver Sacks with Lawrence Weschler

Discovering Oliver

Back in California, he received a copy of Oliver Sack’s Awakenings from one of his professors in college. The book had rave reviews from literary giants, like the poet W.H. Auden and Frank Kermode. Young Lawrence Weschler was astonished at the rare combination of the book. It was a tale about medicine, specifically, patients who had suffered the sleeping sickness of World War I, encephalitis lethargica. The strange thing was, that the prose of the medical book was a reminiscence of Victorian times. The doctor in Awakenings knew his literature, wrote in the first person and tried to not only bring to life the triumph and falls of his practice, but to paint a human face to his previously frozen patients. Yet, all of these characteristics weren’t the traits that astonished Weschler. In his own words, “the figure of the doctor himself was remarkably fugitive, held back, subdued.”

“Oliver Sacks” was the name under the title. Weschler decided to send him a letter, talking about Awakenings and the prospect of “turning his book into a film.” Time passed and it seemed that the letter was lost. But, some months later, Weschler received a reply from Oliver himself. The letter featured Oliver Sacks’ genius nature when talking about his patients, and his generosity on learning about the impact of the book on Weschler. Ren, as Oliver used to call him, went off to develope an extraordinary relationship with his subject. They traveled to London, California, and all over New York to learn about the celebrated doctor’s life.

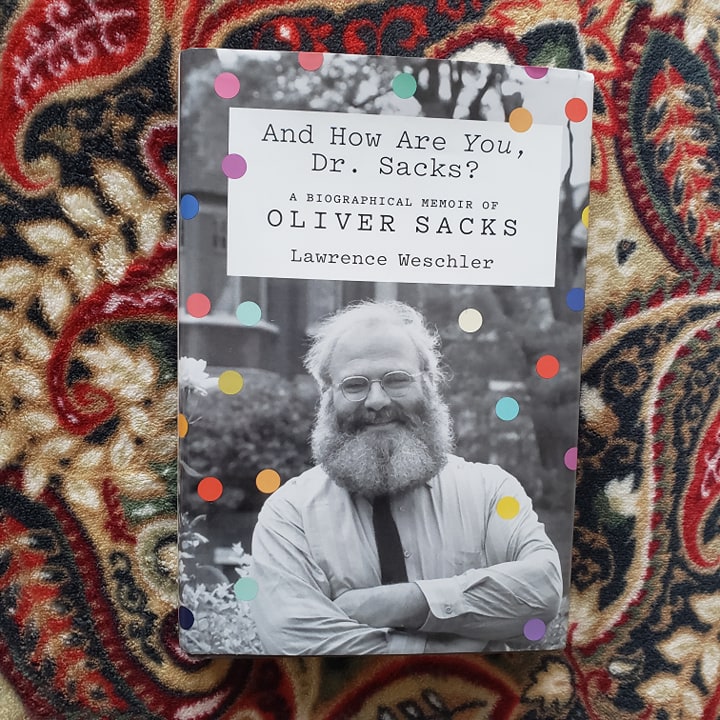

In 1984, Weschler had everything ready for the profile piece, but Sacks asked him not to submit it. The reason? Sacks homosexuality, which he hid for more than 50 years from the public. Fears, insecurities, and a traumatic episode with his mother when he was a teenager made Sacks hide his sexual preference. The author of The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat asked Weschler to remain friends – and indeed they remained. But in 2015, in Sacks’ last moments, Weschler was asked by the doctor to work again on his profile and to publish it. These were the seeds for what is Oliver Sacks’ first biography after his death, And How Are You, Dr. Sacks by Lawrence Weschler (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux).

An Unkown Oliver Sacks

The Sacks that we find in Weschler’s book is unknown to the habitual reader. Here we find the master of the medical prose with just two published books, with neither of them being a commercial hit. We even find out about the failure that was Awakenings in the market. Colin Haycraft, Oliver’s publisher in London at Duckworth (created by Gerald Duckworth, the half brother of Virginia Woolf), goes on to say that he never had a book “with better quotes and better reviews” that didn’t sell. When Weschler interviews Sacks, the book was still on his first printing, which had only 1,500 books. Not even big literary houses, like Penguin, Doubleday, and Vintage, found success with the book.

In most of the pages of Weschler’s books, we dive into what was Sacks’ life in the 1980s. Many things pop up. First, he was struggling with his lesser-known book, A Leg to Stand On. Fans of Sacks will remember that the book was part of a traumatic accident that he had when confronting a bull in the mountains of Norway. Through Weschler’s incisive investigation, we find out about the blockages of Sacks and the possibility that the story could be exaggerated. Indeed, on various pages, we find out a pattern about Sacks: he would elevate the characteristics of his patients or loved ones and exaggerated the “evil” nature of his adversaries. Even his friends, like the late Jonathan Miller and Eric Korn, doubted that it was actually a bull that caused the accident.

The reader that is familiar with Sacks will once again get to revisit the issues that the doctor had in California and New York, like the drug addiction that made Oliver go to psychotherapy for more than 30 years. (Weschler doesn’t know if this is a good thing or if it is telling about the failure pf psychotherapy.) The migraine drama, in which he goes against the wishes of his boss and publishes a book about “migraines” – subsequently getting Oliver fired from the headache clinic – is explained yet again, but with an exploration by Weschler’s perception. Some interrogations by Weshclers are valuable for the reader in the “migraine drama”. The writer doesn’t understand Oliver’s fixation to tyrannical bosses. The book musses in some psychoanalytical territories, on some occasions tracing the route of that problem (the fixation for dictator bosses) to Oliver’s relationship with his mother.

Indeed, Weschler invites the reader to analyze Oliver’s childhood through his lenses. When reading Oliver’s memoirs, Uncle Tungsten (2001) and On the Move (2015), his childhood might seem, at times, like a regular one. In the latter title, Oliver does explore the horrific words of his mother towards him when discovering he was gay. (“You are an abomination. I wish you had never been born” were the exact words of Oliver’s mother.) Yet, is Weschler who makes the reader go deeper into that relationship. How cold was Muriel Elsie Landau? She didn’t notice – alongside her husband – the abuse that Sacks received while on prep-school; she made Oliver (when he was a teenager) watch the dissected cadaver of a girl with the same age as his; she never showed too many emotions to Oliver, who was regarded as gifted, but not the favorite of his family. The ultra-Jewish festivities, the conversations while on the dinner table about surgery, all of this seems odd when presented by Weschler.

What emerges in mid-book, through Weschlers’ insightful writing, is an exceptional doctor, with an unorthodox style, with writer’s blockage and whose character sometimes falls into depression. In a conversation while eating Sushi, Oliver says to Weschler at the time (in 1982):

“For all my failures and the suicide which will probably end it all, I do have a feeling of developing, though, of being different at fifty than I was at forty, at forty than at thirty. I don’t know how people who don’t develop bear it.

I think I’m deeper. I have a stronger sense of depths and abysses and what is surely felt and experienced through difficult to put into words.

But, of course, in fact, I haven’t gone forward. I’ve gone back. I present a sorrier state each decade.” [Italics added by the author]

Oliver was finding it hard in Weschler’s biography to destroy the blockage that froze him from completing his Leg book. Weschler saw how the big, jolly, and voracious giant would attend different clinics while maintaining long and detailed descriptions of his patients. Even though his literary prose was restraint at the time, Oliver never forgot to be a great doctor.

Oliver and the Weschler family

For Weschler, it was Oliver’s sexual preference that might hint his solidarity with his patients. Throughout the book, one finds Oliver immerse in the care and study of his post-encephalitis patients. Later on, he develops an interest in patients with Tourette’s syndrome and much later, the deaf and the autistic. It is strange to find Oliver being conscious of his homosexuality, but not interested in the gay rights movement. As Weschler definitely associates, while the Awakenings drama was happening, in New York, the Stonewall riots were occurring.

Weschler theorizes that the solidarity that Oliver was searching for, he found it in the various movements that supported the identity of his wide array of patients. A bigger sense of belonging was attributed to the Tourreters and the deaf, that in the gay rights movements. (Weschler explains that his involvement with the deaf movement served “at least in some sense as a release valve for some of those internal pressures.”) This strange paradox might be explained by Oliver’s long celibacy. Already in the 1980s, he had started that long journey that stopped when he met his partner, the writer Bill Hayes. He had no interest in the gay rights movement because, at the time, he was basically uninterested in his sex life and still fighting with the ghost of his mother and those infamous words. Indeed, in a final footnote in one of Weschler’s chapters, he reflects the following about the celibacy of Oliver and the AIDS epidemic that swept the country:

“… the catastrophic upsurge, that is, at first trickle but by 1985 a horrendous floodtide, of the disease which would become known as AIDS, and all the crosscurrents of engagement, solidarity, and denial that it was going to bring forth. (over the years, Oliver and I had occasion to note the fact that his own self-enforced celibacy after the mid-sixties, for all its torments, had obviously had the ancillary effect of sparing him exposure to the rampaging disease.)”

It was finally Oliver’s internal conflict with his sexual orientation that made Weschler publish the book 30 years after the fact. “I have come to value you as a dear friend,” told Oliver to Weschler: “I value you more in that role than as any sort of biographer. Although I deny nothing… I have lived a life wrapped in concealment and wracked by inhibition, and I can’t see that changing now. So please I must ask you not to continue. I don’t care what you do with all your material after I die. Just not now.” As Weschler puts it later, “And that was that.”

What is left of Weschler’s book is undoubtedly the happiest moment of the tale. Oliver becomes the godfather of Weschler’s daughter and the family becomes closer. The grimy and depressed figure that is presented in most of the book is substituted by an acclaimed doctor that dress-ups as Santa Claus to bring joy to his goddaughter. Similar to the former books related to Sacks (look for Bill Hayes moving account, Insomniac City), this one ends on a sad note. Yet, one feels that Weschler brought a balanced profile of the man he set out to discover in 40 years ago.