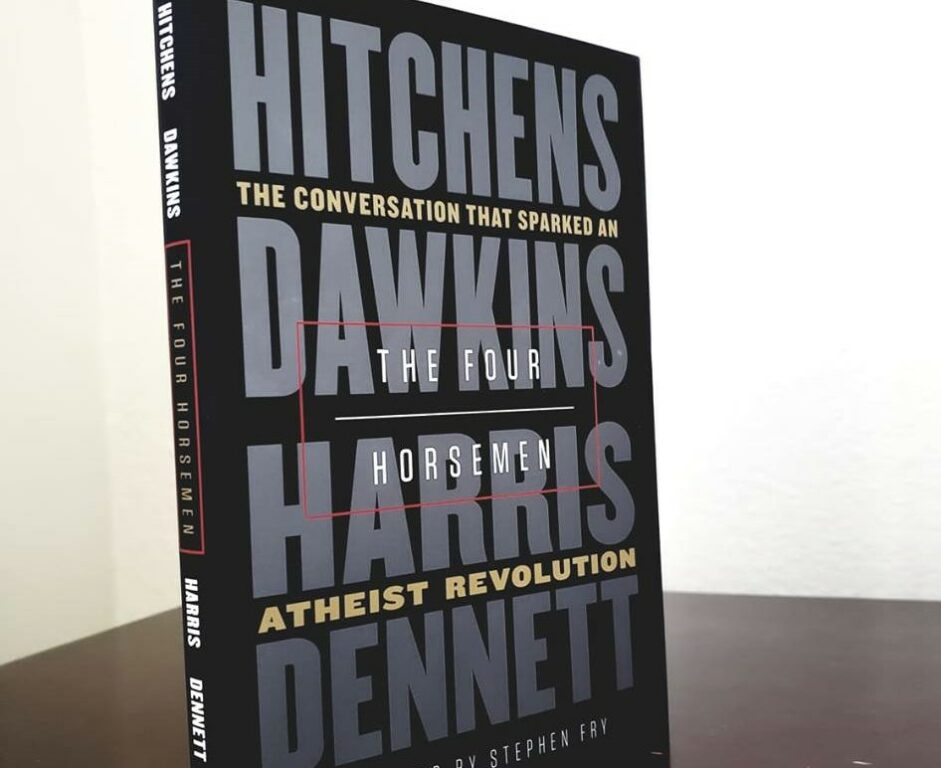

In 2007, four men sat down for a two-hour talk about religion, atheism, science, among other topics. This would have been a cordial and meaningless conversation if it was perpetrated by any other four men. But this wasn’t ordinary men; these were The Four Horsemen of Atheism. At that point in time, these four famous atheists had produced a body of worked that had sparked what we know now as the atheist revolution and for many, this was the beginning of a new type of atheism. The body of work featured five international best-sellers: The End of Faith and Letters to a Christian Nation by Sam Harris (2004 & 2006), Breaking the Spell by Daniel Dennett (2006), God is Not Great by Christopher Hitchens (2007) and The God Delusion by Richard Dawkins (2006). The latter as its author explains is still bought by the thousands and has been downloaded illegally in many Arab countries.

The books by these four horsemen of new atheism were a protest to the policies of the George W. Bush administration and a reaction of what had happened on 9/11. At the time, it was a breath of fresh air. It put religious fundamentalists on notice and countered the theocratic proposals around the globe. These men weren’t the only one pushing the atheist revolution. Personalities like Bill Maher, with his documentary Religulous, and Dutch activist and ex-Muslim Ayaan Hirsi Ali had brought a spark of their own – Ali was supposed to be the fifth member of this famous conversation, but an emergency canceled her appearance.

The conversation was taped and sold by the Richard Dawkins Foundation and was later uploaded to YouTube. The rest was history. Debates all over the country were held, with a variation of the four horsemen against some religious pastors, priests, rabbis or even secular humanists like the case of Robert Wright or Jonathan Haidt. Negatively or positively, new atheism made many question their faith and challenged some long-held views. In more conservative places, it took the weil off a taboo on questioning religion and for some, their long-standing passion for Christ (as was the case by the subjects studied later by Dennett).

Now, 12 years have passed since the conversation between the four horsemen took place. Hitchens, armed with wit and amazingly well-equipped with endless analogies of literature, died of cancer in 2011. Harris, the brash, young companion of the revolution and neuroscientist in-training, started to focus on other issues like free will, artificial intelligence, meditation, among others. Dawkins, the most prominent scientist of the four, is still one of the most recognizable faces in science and one of the most prominent popularisers of science, especially evolution. And Dennett, one of the world’s most famous philosophers, is back to thinking on the hard-problem (consciousness) and other topics, like AI and the evolution of the mind.

What has happened during these twelve years? And, what can we learn from their transcript of the 2007 conversation, published in a new book called The Four Horsemen: The Conversation That Sparked an Atheist Revolution?

New Atheism and its Revolution

Confronting the Atheist Revolution

I too favored the atheist revolution at the time. I was raised Catholic, like many kids on the island of Puerto Rico. My family, especially my father, was deep believers and followers of Catholic dogmatism. My brother cousins and I became altar boys, even serving for the archbishop of San Juan on many occasions. We were enrolled in Catholic schools until college and were obligated to attend mass on Sunday with our whole family. To say that our family was almost fundamentalist is not a far-off statement. Along with God, Catholicism brought bigotry for other religion, sexual preferences and even women rights. As I noted previously, these were the Bush years, and fundamentalism had taken over the military and politics.

It wasn’t until a friend of mine – now the owner of a famous cap brand – brought the DVD of the newly released documentary of comedian Bill Maher, Religulous to our high school religion class. For the record, I’m still debating if he brought it as an accident or if he took advantage of the sister’s (nun) bad English and made her believe that it said religious instead of religulous. At the time, my English wasn’t any good, and I didn’t understand most of the documentary. What made me realized that this wasn’t a religious movie was two nuns performing oral sex on each other at one point.

Luckily, I found the doc on satellite tv at home and sat for two hours as Bill Maher questioned everybody’s religion. Again, one must remember how taboo this was, especially in Puerto Rico. We now take for granted the liberty of criticism to religion, but at the time, it really challenged my core beliefs. I had to watch Religulous at least a dozen times before confronting my faith. This was the fire the ignited the explosion. I started to rave against the sister and protested any dogma inserted at class. This revelation, along with the crazy biological and neural changes that happen to teenagers became a wildfire. I soon went to college and to my good fortune, my humanities and social science professors were on the same page with me. At the same time, I saw an interview with Sam Harris, which prompted me to see all these new atheist debates. At 21, my transition was completed. I was no longer a believer, I was an atheist. But, am I still a new atheist?

The Problem With New Atheism

I asked that question because new atheism became famous for its bravado and up-front challenge to religion. For many, it denigrated the human behind the religion, and some criticized the arrogant conduct when referring to religion. Others find that Harris and Dawkins were too hard on Islam and that they were painting Muslims with a broad brush. Another problem was that many atheists found other aspects of these four horsemen contradictory to their liberal beliefs – it was rare to see a conservative atheist. Hitchens had published an article on Vanity titled, “Why Women Aren’t Funny,” which sparked outrage across the internet. Moreover, he became more and more aligned with the Iraq war, becoming a staunch defender. For Dennett, he himself said it best in his introductory essay of this new book: “For once in my life, I get to play ‘good cop.'”

The prodigious writer and Current Affairs editor-in-chief, Nathan J. Robinson, summarized best the current feeling on the four horsemen:

“The progressive critiques of New Atheism are mainly founded in the New Atheists’ violations of other left-wing values. New Atheism is attacked not solely for being arrogant, but for putting this arrogance in the service of right-wing tendencies like sexism, hawkishness, and bigotry against Muslims. And because leftists believe that holding prejudiced beliefs about women and religious minorities is fundamentally irrational, this makes New Atheists not just obnoxious, and not just right-wing, but also hypocritical: they state that they are committed to reason, logic, and evidence, yet they pervert the meaning of these terms by using them to describe ideas that are not reasonable, logical, or evidence-based.”

Learning from the Atheist Revolution after Twelve Years

So, what can we learn on this now 12-year-old conversation? For myself, I never saw the YouTube clip of it. I didn’t need it to reaffirm that I didn’t need religion. So, when reading this book, it was a whole new experience and I found some little nuggets on how the atheist revolution started.

The book starts with an introduction by fellow atheist and friend of Christopher Hitchens, Stephen Fry. The comedian, filmmaker and writer opens-up on how this conversation and group of atheists dug a hole into religion. As Fry says in the foreword, “The emperor had been parading about for centuries, and it was time someone pointed and reminded the world that he was naked.”

After a brief introduction, we move on to the essays by the living members of the original group. Dawkins opens first with the longest essay of the three, explaining the “irrationality” of religion. He paints two distinct pictures, one on religion and another on science, explaining the achievements of the latter and the obsoleteness of the former. He ends by stating, “As an atheist, you abandon your imaginary friend, you forgo the comforting props of a celestial father figure that bail you out of trouble.” Dennett’s essay is less accusatory and more in the mode of how individuals can change their isolated worlds and “break the spell of religion.” Harris, on the other hand, criticizes the idea of God with the story of a woman in Brazil getting bitten by the mosquito with the Zika virus.

The Conversation that Ignited the Atheist Revolution

The conversation starts with similar talking points heard in other debates. They first talk about the arrogance of religion and the way many who are religious play the victim card. Other topics include Islam, the criticism of their books, religious dogmatism, the way that religion can be harmful and other known counterpoints.

Finally, some interesting points start to pop out. For example, they get into the topic of faith by the congregation on their pastor and faith in scientists. I have seen this argument play out on many occasions when religious people will tell a scientist or atheist that they too rely on faith when favoring science. Dawkins sheds light on this argument by explaining the process of reviewing science – peer review, competition, etc. – and how pastors or religious leaders don’t take that same steps.

Hitchens adds to the conversation on how exact science can be in contrast with religion:

“No religious person has ever been able to say what Einstein said – that if he was right, the following phenomenon would occur off the west coast of Africa during a solar eclipse. And it did, within a very tiny degree of variation. There’s never been a prophecy that’s been vindicated like that. Or anyone willing to place their reputation and as it were, their life on the idea that it would be.”

Another eyebrow-raising point in this conversation is Dawkins admitting that he wouldn’t want to be ignorant of the bible. Even Hitchens replies by exclaiming, “No, very right!” Dawkins then adds, “you cannot understand literature without knowing the Bible.” He adds that you can’t understand music or history reasons without it. Even when Harris challenges the point, Dawkins replies, “You can more than just appreciate it. You can lose yourself in it, just as you can lose yourself in a work of fiction without actually believing that the characters are real.” Moreover, Dennett and he agree that churches are great places to enjoy weddings, funerals, poetry, music, and even group solidarity. This is a big contrast to the image many paint of the four horsemen.

Last Word on The Four Horsemen and the Atheist Revolution

The Four Horsemen is a book worth reading if you don’t want to lose yourself in all the articles depicting and delivering accusations to the atheist revolution. As scientists say, always go to the original paper, or in this case, the original conversation. It is true that the atheist movement changed drastically, and its proponents have gone in different directions. Moreover, others have joined the group, as the psychologist Steven Pinker and the biologist Jerry Coyne. But you don’t have to agree with the person or all their talking points to see their brilliance and impact on demystifying religion. The Four Horsemen is a needed reminder on how long we have come and what ignited the fire on many. Although its originals do have some rightly deserved criticism, it relies on the fact that religion keeps going down in the US and around the world.