In February of 2016, independent studio A24 released a horror film titled The Witch. The film was met with critical acclaim but did not play nearly as well with general audiences. The following year, they released It Comes at Night to much of the same response. Finally, this past month, a film by the name of Hereditary was released. It received heaps of praise on the festival circuit and even drew comparisons to The Exorcist. Upon theatrical release, critics echoed that same level of praise; however, the response of general audiences was still lukewarm. What, exactly, is causing such a consistent variance in the reception of these recent A24 releases? The answer may lie in the connecting thread among these three films: the psychological horror subgenre.

(WARNING: Spoilers ahead for all films involved)

The Rise of Psychological Horror

What is Psychological Horror?

Before delving into this topic, it is necessary to first identify what exactly defines the parameters of the psychological horror subgenre as well as some of its common characteristics. In its most basic form, a psychological horror film is a relatively grounded, character-driven affair. The story is often told through the point of view of one of the characters as a means of bringing out the very real psychological or emotional fears that are deeply rooted in the human psyche. This results in an overall sense of dread or unease for the viewer, rather than a blatant scream fest. Horror filmmakers are able to achieve this effect in a variety of ways.

One of the key characteristics found in nearly every successful psychological horror film is the self-doubt of the central character. They often have different perceptions of their surroundings than other characters in the story and, when they find themselves unable to properly justify their mindset, they begin questioning their own sanity. The audience often doesn’t know anything outside of what is perceived through the eyes of the main character. When the filmmaker purposely avoids answering a lot of the questions posed by the main character and shining a light on the unknown, that sense of uncertainty is then transferred over to the audience. That brings us to one of the most common fears that the subgenre plays on: the fear of the unknown.

Fear of the unknown or unseen relies on the creativity of our own minds. It’s the prevailing theory in psychological horror that when something isn’t shown on screen, your mind will automatically create the most terrifying image that you can conceive. It is a technique that filmmakers use to subvert the subjectivity of horror and allow the audience to draw their own conclusions revolving around what is most frightening to them. This is part of the reason why filmmakers in this subgenre often show a great deal of restraint when deciding what should be shown on screen.

One of the more recent and effective uses of this was done by James Wan in The Conjuring. In the film, there is a scene where one of the young girls, played by Joey King, sees a figure in the doorway of the bedroom she shares with her sister. You see her face fill with fear and know whatever she sees is terrifying; meanwhile, her sister doesn’t see what she sees and neither does the audience. Everyone likely pictures a different apparition in the doorway, the apparition that would be most terrifying to them. Without even putting a figure on screen, Wan crafted one of the most terrifying scenes in the film.

Psychological horror films usually don’t rely on gratuitous violence or gore to achieve their desired effect. You won’t find any CGI monsters or cheap jump scares. The subgenre relies more on atmosphere and subtlety. These films, more often than not, are aesthetically gloomy and overbearing. There is often a high level of tension, built slowly over time, both between the main character and others as well as in the internal conflict that the main character is often battling. For this reason, films in this subgenre are often low-budget affairs.

From Humble Beginnings to Film Royalty

In the early days of horror, filmmakers didn’t have major budgets to work with or have the option of computer-generated imagery to enhance their scares. They had to find techniques in which they could scare audiences in a practical and inexpensive manner. Among the fruits of their efforts rose the subgenre of psychological horror. A subgenre of films that preys on everyday fears. Fears that don’t need expensive effects in order to be exploited. These films employed a deep understanding of the human psyche to generate tension and often reveled in their own ambiguity. What resulted was some of the most notable and widely praised films of all time, not just in horror.

Rosemary’s Baby

One of the pioneer films in the psychological horror subgenre is Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby. This film tells the story of a woman who believes some creepy individuals in her life may be tampering with her pregnancy. It garnered widespread acclaim, both critically and commercially, and is considered a classic in the horror genre. In its two-hour runtime, it tackles many different fears individuals commonly possess, including the natural fear and sense of uncertainty that comes with pregnancy, the sense of claustrophobia that can be brought on by urban living, and the fear of not being in control. Tapping into such real fears can only be achieved by telling a grounded, believable story that the audience can buy into.

In Rosemary’s Baby, one of the filmmaking techniques Polanski uses to achieve this is called Mise-en-scène, which is characterized by the constant use of long takes and supported by masterful cinematography and set design. Polanski uses this style of filmmaking to give the audience a sense of the space in which the majority of the film takes place (in this case Rosemary’s apartment). He also uses it as a means to allow the audience to connect with Rosemary as most of these takes are seen from her point of view. The audience only sees what she sees and only know what she knows, which plays beautifully into that “fear of the unknown” aspect that is so deeply rooted in the subgenre. The constant intrusion of her neighbors into her life combined with the consistent use of close-ups adds to the sense of claustrophobia in the film. That same constant intrusion by her neighbors, along with seemingly everyone telling her what to do and Rosemary’s submissive attitude towards them, adds to the sense of a loss of control.

In the end, it is revealed to both Rosemary and the audience, that she was being manipulated by everyone around her (including her own husband) into carrying and birthing the literal spawn of Satan. Polanski makes the creative decision to never show the baby on screen, even after Rosemary looks on in horror. By not showing anything explicitly and leaving a number of questions opened ended, Rosemary’s Baby diverts from making the focus of the story this possible spawn of Satan and keeps the focus on Rosemary’s fears and paranoia. This allows audiences to develop their own interpretations and dramatize their own fears in the context of the story. It also invokes the fear of the unknown, allowing the viewer to paint their own terrifying picture of what was in that crib. Whether what you fear is something as simple as the unknown, or something as complex as the fears that come with pregnancy, or even something as socially relevant as the ongoing struggle of women in modern society, Rosemary’s Baby exposes it along with many others.

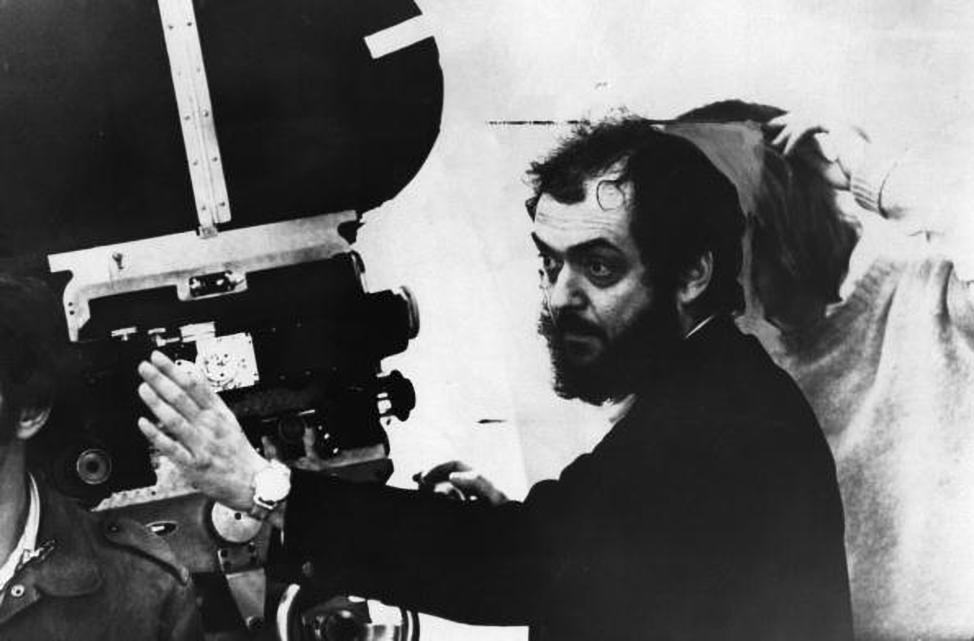

The Shining

Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining is another staple of psychological horror and oftentimes considered one of the scariest, if not the scariest, movie ever made. Unlike Rosemary’s Baby, this film actually does show some paranormal entities on screen, but its true horror is brought on by Jack Torrance’s descent into madness and the overall feeling of claustrophobia brought on by being trapped in the Overlook Hotel with a murderous psychopath. Jack’s treatment of Wendy and his eventual murderous rage against her dramatizes a very real fear of domestic violence. The sense of claustrophobia combined with the domestic violence aspect of the story grounds it in a sense of realism, despite the supernatural elements, and allows the audience to connect with the characters and truly drive the fear home.

Speaking of the characters, the ability to make the audience connect with and be empathetic towards the characters is what makes The Shining stand out among similar horror films. One of the common examples used when discussing this movie is a scene towards the end of the film involving Wendy and Jack on a staircase. In the scene, Wendy is seen wielding a baseball bat as Jack slowly and menacingly walks up the stairs towards her. She’s swinging it back and forth as if to ward him off rather than make contact. At this point in the film, the audience has connected with Wendy and is empathetic to her situation. So, instead of the tension revolving on whether or not she can make contact and strike Jack, the tension instead revolves around whether or not she would actually hit her husband with a baseball bat. While the former is more a characteristic of slasher films, the latter is the type of tension only a character-driven narrative can bring.

Much like Rosemary’s Baby, and other films of the subgenre, The Shining revels in ambiguity and opens itself up to interpretation. There is even an entire documentary, Room 237, that is dedicated to different interpretations and theories about the film. However, unlike other films in the subgenre, fear of the unknown does not play a major role here. Most of the ambiguity and different interpretations pertain to the meaning of certain smaller moments and the potential broader, overarching themes of the film.

Rosemary’s Baby and The Shining are truly the cornerstones of the psychological horror subgenre as well as iconic entries into the overall horror pantheon. Other notable psychological horror films include Roman Polanski’s Repulsion, Peter Medak’s The Changeling, and many of Alfred Hitchcock’s greatest works. However, as the 1980s came along, it brought with it a significant shift in the genre. A shift that would introduce special effects into the fold and give rise to more gratuitous forms of filmmaking in horror.

(To be continued in part two)

Main Image Credit: